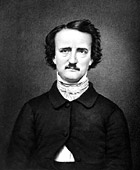

EDGAR ALLEN POE was born in Boston, January 19, 1809, and after a tempestuous life of forty years, he died in the city of Baltimore, October 7, 1849.

His father, the son of a distinguished officer in the Revolutionary army, was educated for the law, but having married the beautiful English actress, Elizabeth Arnold, he abandoned law, and in company with his wife, led a wandering life on the stage. The two died within a short time of each other, leaving three children entirely destitute. Edgar, the second son, a bright, beautiful boy, was adopted by John Allen, a wealthy citizen of Richmond. Allen, having no children of his own, became very much attached to Edgar, and used his wealth freely in educating the boy. At the age of seven he was sent to school at Stoke Newington, near London, where he remained for six years. During the next three years he studied under private tutors, at the residence of the Allen's in Richmond. In 1826 he entered the University of Virginia, where he remained less than a year.

After a year or two of fruitless life at home, a cadetship was obtained for him at West Point. He was soon tried by court-martial and expelled from school because he drank to excess and neglected his studies. Thus ended his school days.

In 1829 he published "Al Aaraaf, and Minor Poems." "This work," says his biographer, Mr. Stoddard, "was not a remarkable production for a young gentleman of twenty." Poe himself was ashamed of the volume.

After his stormy school life, he returned to Richmond, where he was kindly received by Mr. Allen. Poe's conduct was such that Mr. Allen was obliged to turn him out of doors, and, dying soon after, he made no mention of Poe in his will.

Now wholly thrown upon his own resources, he took up literature as a profession, but in this he failed to gain a living. He enlisted as a private soldier, but was soon recognized as the West Point cadet and a discharge procured.

In 1833 Poe won two prizes of $100 each for a tale in prose, and for a poem. John P. Kennedy, one of the committee who made the award, now gave him means of support, and secured employment for him as editor of the "Southern Literary Messenger" at Richmond. After a short but successful editorial work on "The Messenger," his old habits returned, he quarreled with his publishers and was dismissed. While in Richmond he married his cousin, Virginia Clem, and in January, 1837, removed to New York. Here he gained a poor support by writing for periodicals.

His literary work may be summed up as follows: In 1838 appeared a fiction entitled "The Narrative of Arthur Gorden Pym;" 1839, editor of Burton's "Gentleman's Magazine," Philadelphia; next, editor of "Graham's Magazine;" 1840, "Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque," in two volumes; 1845, "The Raven," published by the "American Review;" then sub-editor of the "Mirror" under employment of N. P. Willis and Geo. P. Norris; next associate editor of the "Broadway Journal."

His wife died in 1848. His poverty was now such that the press made appeals to the public for his support.

In 1848 he published "Eureka, a Prose Poem."

He went to Richmond in 1849, where he was engaged to a lady of considerable fortune. In October he started for New York to arrange for the wedding, but at Baltimore he met some of his former boon companions, and spent the night in drinking. In the morning he was found in a state of delirium, and died in a few hours.

The most remarkable of his tales are "The Gold Bug," "The Fall of the House of Usher," "The Murders of the Rue Morgue," "The Purloined Letter," "A Descent into Maelstrom," and "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar." "The Raven" and "The Bells" alone would make the name of Poe immortal. The teachers of Baltimore placed a monument over his grave in 1875.

Poe has been severely censured by many writers for his wild and stormy life, but we notice that Ingram and some other prominent authors claim that he has been willfully slandered and that many of the charges brought against him are not true. His ungovernable temper and high spirit led him into disputes with his friends, hence he was not enabled to hold any one position for a great length of time. Like Byron and Burns, he had faults in personal life, but his ungovernable passions are sleeping, while the sad strains of "The Raven," the clear and harmonious tones of "The Bells," and the powerful images of his fancy live in the immortal literature of his time.

Biography from: http://www.2020site.org/literature/index.html |